The Exodus of Kashmiri Pandits: A Tragic Tale of Forced Migration

The eruption of militancy in 1990 created a situation that is difficult to even imagine now, thirty years down the road. The situation had restricted reportage in Srinagar and everyone was in survival mode when the exodus of Pandits took place. However, this facet of the Kashmir tragedy was well documented by the resourceful Delhi media. Here are three detailed reports that appeared in three major publications outside Kashmir.

Migrating To Safety

India Week, February 15-19, 1990

Aasha Khosa reports from Jammu on how intimidated, terror-stricken non-Muslims from Srinagar have come down to the region after the recent wave of violence in the valley.

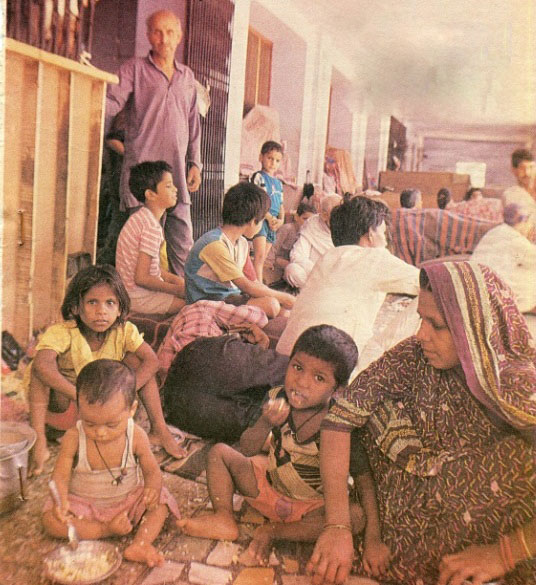

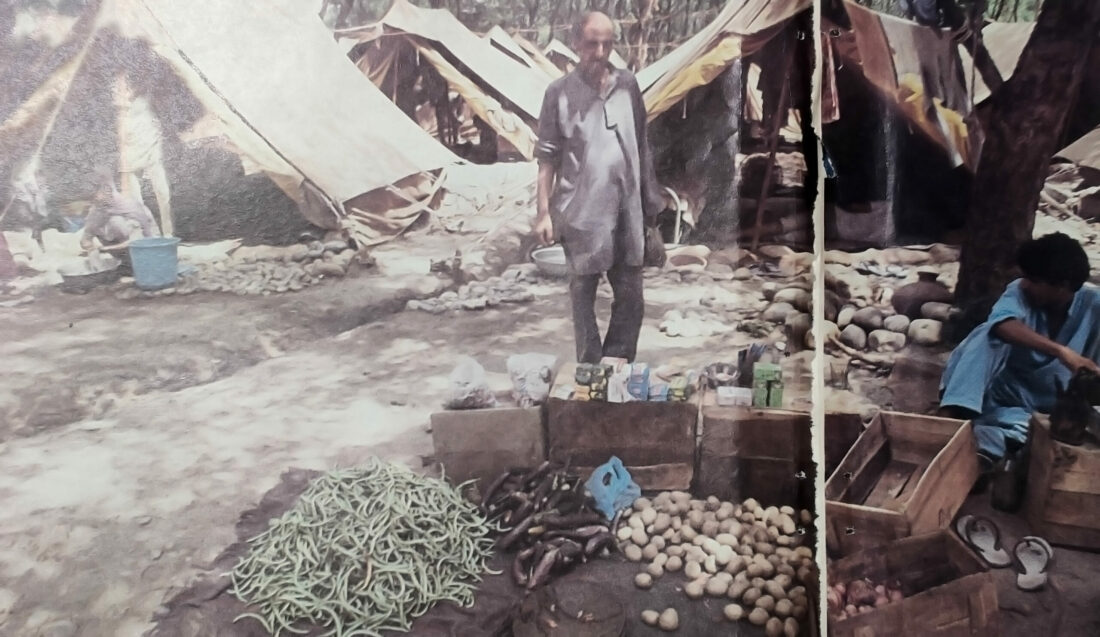

Even while they toil day in and day out searching for shelter and the means to rekindle their hearths, the memories of that night still haunt them. About 2,000 families from both the rural and the urban areas of Kashmir valley have moved down to Jammu for what they call “permanent settlement”. Leaving behind their homes, property and even jobs, these migrants, mostly Hindus, are still under the spell of fear which has gripped the valley till yesterday virtually ruled by the pro-Pak militants.

Without disclosing their full identity, some of them narrated the experiences, which led to the mass exodus. Manisha, a 21-year-old post-graduate lived in a palatial bungalow in Srinagar city’s Magarmal Bagh locality. She and her parents escaped from Srinagar in a luggage truck. Manisha said: “The deafening calls on loud speakers, probably fitted in the mosque near our house, are still fresh in my mind. Allah-o-Akbar and other Islamic slogans rent the air. Even though the militant tone of the slogans was scary, we consoled ourselves that it did not mean any harm to the non-Muslims. But then, suddenly, some immature and young voices besieged the megaphone system and then there were slogans calling for raiding the houses of non-Muslims.”

Her mother adds: “In the absence of a male member in the family – they had gone in hiding to avoid participation in the rally to be held against curfew restrictions – we were scared. I bolted the house and locked my daughter in a room. To tell you honestly, I was even prepared for self-immolation in case the threats issued from the loudspeakers were realized.” Manisha is looking for a job and is sure she will never go back.

Abducted

A young employee working with the wireless section of the state police as a technician is reluctant to recall his experience for fear of retribution from the militants. Three masked men broke into his house in a downtown locality in broad daylight and asked him to go along with them. At gunpoint and in the presence of all his family members, he was taken away. He returned after three days. In the meantime, the family was too scared to even report the matter to the police. They did not dare disclose the matter to even close friends. “All we did was hope against hope,” said his brother.

Another employee of the post and telegraphs department in Srinagar recalls how he was beaten up by some urchins when they found him loitering around on the bundh. He was taken to the mosque and kept there for the night. “I sat in a corner while the huge congregation, mostly comprising young boys, raised militant slogans throughout the night. In fact, the atmosphere inside became such that I began fearing for my life. Next day, I, along with others, was taken outside to march in a procession protesting against the curfew orders.”

Reports pouring in from Srinagar, along with the accounts of the people who have shifted out from there, suggest that the militants had mobilized the public for the January 21, protest against curfew restrictions by selling them the idea that it would be the final showdown between them and the government. The latter, on the other hand, has started justifying its existence of late. At least 30 people were killed on the day when paramilitary forces opened fire on the mobs defying curfew restrictions in various parts of the city. “The militants did not show up,” lamented a citizen of Srinagar’s walled city who felt humiliated to have been taken in by the militants’ propaganda.

Militant slogans

Another young girl belonging to one of the Hindu-dominated downtown localities said: “Even now when I think of that night, a shiver runs down my spine. (The night she and the others are referring to is the one preceding the day when 30 persons were killed when paramilitary forces fired on mobs defying curfew orders). All the women in our locality were huddled together in a room as the mikes-fitted in the mosque started blaring out militant slogans. We reinforced the bolted door with more nails to delay the forcible entry of the raiders. We all wore sports shoes and searched for an escape route.” However, nothing happened.

The next day the girl was packed off with a number of other women in a taxi to Jammu. She is staying there with a relative, waiting for her parents to join her.

In the villages, the story is even worse. The last time the villagers had deserted their homes in search of security in the city was in 1947-48 when, in the wake of raids from the Pakistani infiltrators, they had moved to Srinagar city. The first time communal riots broke out in the entire Kashmir valley was when a Muslim boy married a Hindu girl.

This time, initially, tension prevailed in Anantnag town and the villages surrounding it. However, soon the tension percolated down to all the villages in the valley and, according to the migrants, at many places religious places were used to fan propaganda against the government and, at places, against the non-Muslims. In a particular village of Badgam district where there are only three non-Muslim families, there were threats of “axing them to death”. Said a young housewife of that village: “No doubt every Muslim in the village assured us of help in case anything did happen, but, I think, they too would be too scared to act in such an eventuality. So we decided to move.”

Muslims, too

But it should not be inferred from all this that only the non-Muslims are in the grip of the fear which, despite governor Jagmohan’s assurances, still pervades the Kashmir valley.

According to reports, even Muslim families have shifted their women to safer places and taken all measures to ensure their safety. The worst-affected are children who are confined to their houses thanks to the disturbances and curfew at a time when they should be enjoying their annual winter vacations.

Said a young Muslim who is looking for accommodation in Jammu: “It is easier for the non-Muslims. At least they feel secure in Jammu, the Muslims are tied down to Kashmir valley. The affluent Muslims who fear a Hindu backlash in Jammu can safely move to Delhi or other places. But what about the less affluent?”

According to reports, a number of government employees working in state and central intelligence set-ups want to be moved out from the valley. They have all applied for transfers. The central departments, too, are facing similar problems, thanks to the militants’ call for boycott of the central services and their threat to; women employees to quit since “Islam does not allow women to work”. The central departments, however, are sitting pretty over the innumerable applications for transfers out of the valley. According to sources, Jagmohan has issued instructions to the state authorities not to transfer anyone for such a reason. Yet state measures for their rehabilitation are yet to be pronounced.

Flooded

The exodus from the valley has added to the problems in Jammu. Normally, the winter capital of the state is flooded with people from Kashmir during the biennial move of the government. But, this year, the situation is different.

This year the Kashmiri’s are too busy hunting for shelter and jobs to be overjoyed at the change of scene. Every day, state road transport corporation buses and private taxis bring loads of Kashmiri’s to Jammu while the outgoing traffic from Jammu comprises mostly Muslims, mostly the families of employees who move along with the government.

Accommodation is scarce and, as a result, rents of private houses have gone up. No governmental help, not even a voluntary organization has come forward to help these migrants. The Shiv Sena, quick to exploit the situation, did make an offer, but the migrants have discreetly avoided their help. “The situation in the valley will deteriorate further if we let anyone raise the issue here,” said a young journalist who, too, has abandoned his home in Srinagar and shifted here.

An Alarming Exodus

India Today, March 31, 1990

Kashmiri Hindus flee the valley creating a communal crisis

by Pankaj Pachauri in Jammu with Nisha Puri

In 1947, when Pakistani raiders pillaged the homes of Kashmiri Hindus, Sohan Lal was a seven-year-old child in the border district of Kupwara. He lost his father and eight relatives before fleeing to Srinagar. He returned home after two years. The neighbourhood mason, carpenter and shopkeeper- all Muslims – helped him start afresh. He became a teacher in the local school and lived with his family in a house which, over the years, expanded to 15 rooms.

Last fortnight, Sohan Lal fled Kupwara again. There was no raid on his house. No killings. Not even a threat. But when after Shivratri, his relatives from Anantnag and Srinagar did not visit him as they had done every year, Sohan Lal panicked. He locked up his house, gave the keys and his cattle to a Muslim friend and departed with nine other families for a relief camp in Jammu. Says Sohan Lal: “There was no communal tension. It took us six days to leave everything because of fear. And we cried – my family and that of my Muslim friend.”

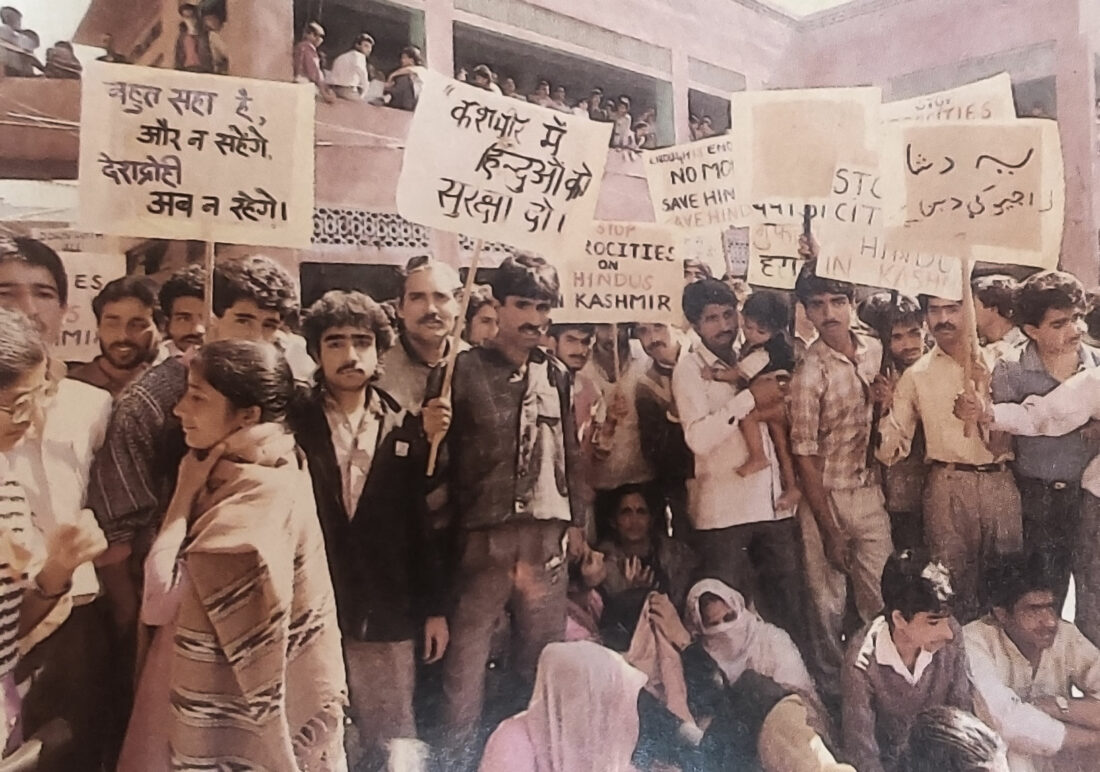

On his third day in Jammu, Sohan Lal was exposed to an alien phenomenon. He was part of a 10,000-strong procession led by VHP acting President, Vishnu Hari Dalmia. As the protestors wound their way through the streets of Jammu, the sloganeering became distinctly communal. “Security for Hindus in Kashmir” and “Down with Pakistan” soon gave way to “Har-har Mahadev” and “Bharatvarsh main rehna hoga, Vande Mataram kehna hoga” (If you want to live in India, you have to chant Vande Mataram). If there were any doubts that RSS cadres had taken over the demonstration, they were put to rest when a placard that read “Down with Indian secularism” was raised. Sohan Lal had never heard such a communal outburst.

But Sohan Lal was just one among over 10,000 Hindu families, which have left the valley – and whose insecurities organizations like the RSS and VHP are trying to exploit. And should they fall into the net of communal propaganda, they can reverse the political efforts for normalizing the Kashmir crisis. Says Home Minister Mufti Mohammad Sayeed: “We can’t afford more complications.” Adds an IAS officer in Jammu: “Our hands are full with the migrants. The last thing we want is a communal flare-up.”

In fact, by the time the all party delegation reached Srinagar, about 40,000 people had reached Jammu, 2,500 Udhampur, 600 Kathua and about 2,000 Haridwar and Delhi. In each of the dozen filthy camps in Jammu and in the decrepit Kashmir Bhawan in Delhi, most refugees said that though they were initially reassured by Jagmohan’s installation as governor, the militancy was unstoppable. Said a doctor from Srinagar: “How can we raise slogans for Islamic rule or say Pakistan zindabad?” Understandably, the militant’s movement has isolated the valley’s 1.2 lakh Hindus.

Fleeing from the stranglehold of Muslim militants in the valley, many of the migrants have landed straight in the lap of Hindu fundamentalists. These groups choose to ignore the fact that many Muslims too have fled the valley because of crippling curfews and breakdown of the administration. In Delhi itself, dislocated Muslims from the valley can be seen hawking the famed Kashmiri shawls and carpets. But such facts do not fit in, with the Hindu fundamentalists’ perception of the Kashmir problem. So at the refugee camps, they are spreading rumours that the militant movement is directed against non-Muslims; that militants are infiltrating camps to identify migrants.

So far, the administration has turned a blind eye to the communal propaganda. For instance, though Dalmia and other VHP leaders went to Jammu to sympathise with the refugees, they ended up exhorting them to support their cause. Said Dalmia at a public rally: “Why does VP Singh run to Bhagalpur with a Rs 1crore cheque? The money was distributed only among Muslims. He should come here with a Rs 2.5 core cheque.”

In a knee-jerk reaction, Jagmohan recently announced two new posts of relief commissioners and stated that camps would be set up in the valley itself and that government employees and pensioners forced to flee their homes would receive their money regularly. But such steps amounted to locking up the stable after the horse had bolted.

Many of the militants too are unhappy with the flight of Hindus. The Jammu & Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF), in particular, realizes that an exodus on communal lines would eventually discredit their movement. In a written statement, four area commanders of JKLF recently offered to “retire” from the secessionist movement if it was “proved by an independent agency or media that they killed anyone only because he was from a particular community”.

An added twist to the problem is the hostility towards the migrants from some Jammu residents. Many Jammu Hindus harbour age-old prejudices against Kashmiri pandits who they believe corner all crucial government